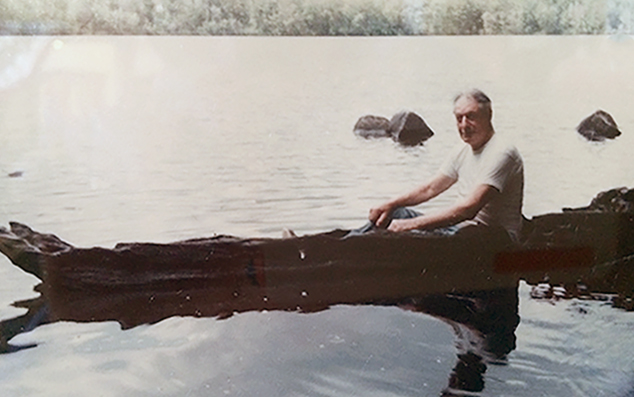

The “Settler’s dugout canoe” rests prominently on display in the Andover Historical Society Museum and holds pride of place in the Society’s history, too. Its recovery from Adder Pond (also known as Hopkins Pond) in 1982 was the catalyst that prompted the creation of the Society, and in recognition of that fact the dugout canoe is listed as the Society’s very first acquisition – Accession No. 82.1 (the “82” stands for 1982, the year the AHS was founded). The canoe merits this attention: it is a very fine and very rare example of a utilitarian watercraft once common across much of North America since pre-Columbian days that most people today have heard about but few have ever seen.

In recent years, many old dugout canoes have been recovered from the bottoms of lakes in southeastern American states, most notably Florida, where more than one hundred were found in a single large lake near Gainesville during a 2000 drought. But in New Hampshire, conditions are much less favorable for their preservation, and very few dugout canoes have been recovered here. In addition to the Andover Historical Society’s specimen, others are on display in the New Hampshire Historical Society (Concord), the Hopkinton Historical Society, the Libby Museum (Wolfeboro), the Millyard Museum (Manchester), the Derry Historical Society, and the Sandwich Historical Society – a total of seven, some of which are hardly more than fragments of the original craft.

What can we determine about the age and provenance of these dugout canoes? Only three on exhibition, those in the New Hampshire Historical Society, the Hopkinton Historical Society, and the Sandwich Historical Society, have been scientifically tested. The former, which had been recovered from Lake Ossipee ca. 1840, is made from a pine tree (a common wood for New England dugouts, although many other kinds of trees were used, too), and radiocarbon analysis dates it to 1430-1660 A.D. Almost certainly, then, this one is an indigenous, Amerindian craft. The latter two, also made from pine trees, were not old enough for such analysis to be very informative, and were simply determined to be post-1750 or post-1800 crafts.

But while the Indians native to New Hampshire certainly made dugout canoes, the early Euro-American settlers of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries quickly adopted the tradition and began making such canoes themselves; and almost all surviving dugout canoes discovered in New England date from the period when both Indians and Euro-Americans were making and using them – a comparatively recent period of time, moreover, when radiocarbon dating is unreliable anyway. How can we determine which are which?

The question can be a complicated one for dugouts found in regions such as Southern New England, where indigenous tribes and colonial settlers lived for many decades in fairly close proximity to each other and with frequent interaction. In midstate New Hampshire, however, an area settled a century or more later, such cultural coexistence was much less common – was, in fact, quite rare. That fact is reflected in our local landscape. Consider this, for example: why is it that Andover ̶ in the state distinguished by such names as Passaconaway, Sunapee, Winnisquam, Nashua, Amoskeag, Contoocook ̶ has (with the possible exception of Adder Pond itself, which may well derive from “attuck,” an Indian name for “deer”) no Indian place names? The answer is simply that, by the time the first settlers moved into this area, the native inhabitants had long since been completely driven out. For some time, the Province of New Hampshire had been pushing frontier settlements – rows of new townships, running roughly in east-west tiers, stretching from the Pemigewasset River to the Connecticut River – northward as a line of defense against the Indians and the French. The towns ranging from Boscawen, Warner, and Bradford to the west were established beginning in the late 1730s and 1740s; the next row north, from Salisbury westward to Newbury and beyond, in the 1750s and 1760s; and the row north of that, from Andover west to New London and beyond, in the 1760s and 1770s. Indian settlements and even Indian incursions retreated steadily northward as these ranks of frontier settlements advanced. Rare Indian raids by marauding bands from French Canada continued in this area into the 1750s, but already by then all the indigenous native tribes had migrated north, most of them all the way into Canada; and Great Britain’s complete defeat of Canada in 1759-60 effectively eliminated the Indian presence in New Hampshire.

Supplementing our historical knowledge about the lack of any overlap of Indian and Euro-American settlements in this part of New Hampshire, we can add important information derived from the design of the AHS dugout canoe. Indian and Euro-American construction methods for dugouts differed greatly. The Indians felled a tree using fire and stone axes and then hollowed it out by a long, repetitive process of carefully burning out the middle of the log with heaped coals for a while, then scraping out the layer of newly charred wood with stone scrapers. Euro-Americans instead used metal axes and adzes to do the same work; they might also use saws to fell the tree or to rough-shape the boat’s stern. These differing construction techniques produced canoes of distinctively different outlines. As one authority summarizes, Indian dugout canoes “tend to have rounded ends and less angular appearance” (the New Hampshire Historical Society’s specimen is a good example of this), while those built by Euro-Americans “are more likely to have a pointed bow and a square or truncate stern” – shapes quite difficult to form with stone tools but much more easily managed with metal tools and indeed (for a squared or truncated stern) very easily produced with a saw.

The Andover dugout canoe, as you can see from the accompanying photographs, has a dramatically truncated stern. (So do the canoes in the Hopkinton Historical Society and the Libby Museum.) This prominent detail immediately does much to date it: If it is of Euro-American construction, and so cannot have been built until this area was first being settled by the town forefathers – that is, not earlier than the 1760s.

But surely we can narrow the date of our canoe’s construction even more precisely than this. Here is another historical consideration: Why did dugout canoes, once so widely known, fall out of use? The most significant factor in their obsolescence, more fundamental even than issues of their great weight, delicate balance, or relative lack of maneuverability, is obvious: Even with metal tools, it took an enormous amount of time and labor to make one. Consequently, dugout canoes started disappearing from the scene, like horse-drawn carriages after the advent of the automobile, when technology changed – specifically, when accessible sawmills made it relatively easy to obtain the milled wood necessary for building a small, lighter, more stable boat much more quickly and at very little expense.

A new town in the New Hampshire wilderness could hardly attract settlers without a few very basic improvements – chiefly a passable road, a sawmill, and a grist mill. The original charter for the future town of Andover therefore made provisions for the immediate establishment of a sawmill to “Saw the Logs & timber of the . . . Inhabitants or such as are preparing to build there.” But this was much easier said than done. The charter was written in 1751, but the first settlers did not arrive until ten years later, and for years after that the little settlement still had no sawmill, despite various half-hearted attempts to site and build one, prompting finally a complaint from the stifled little community that the proprietors had not fulfilled their pledges: “they Clear us no rodes build us no bridges indeed they have built us a saw mill but that not being Completed as it ought to be that we get our bords with a great deal of Difikelty. . . . [T]hese and such like difikeltys and many more . . . is the grate means why people do not settle in the town.” This was in 1767. By 1768 the new sawmill was operating (some distance below the outlet of Loon Pond, now Highland Lake), but only barely, due at least in part to its “standing in an Improper place,” apparently with a greatly inadequate head of water. The mill was eventually moved further upstream, but continued to be a sore issue: Even in 1772 “great complaint was made that [the mill operator] neglected to saw the logs brought to the mill, as he had agreed to do.” The sawmill remained a problem for the town until perhaps as late as 1780. A few years later (ca. 1785), another sawmill was built at Cilleyville. Several other smaller ones were built in later years.

It seems reasonable to conclude, then, that sawn boards were a very rare commodity in Andover in the early decades of settlement, but that by 1785, at the latest, they were sufficiently available so that no reasonable settler would go to the immense trouble of fashioning a dugout canoe when he could so much more easily and inexpensively obtain the boards with which to build a small fishing boat instead. Almost certainly, Andover’s “settler’s dugout canoe” dates from the narrow period 1763-1785.

****************

A coda: Andover once boasted of other dugout canoes as well.

As Ralph Chaffee reported in his History of Andover, New Hampshire 1900-1965, townspeople early in the twentieth century knew of not one but “two waterlogged dugouts sunk in Hopkins Pond” – and had known of them, indeed, for many decades. “Arthur Woodward [born in 1882] . . . remembers them as a boy, and was told by another old resident that they looked just about the same when he too was young.” (So John Lessard, a retired carpenter from Hopkinton, NH, who noticed the submerged dugout while fishing there in 1980 and then mobilized its recovery from the pond in 1982, was by no means its first discoverer, although he would not have known this.) Woodward told Chaffee about the second dugout in Adder Pond and said he was sure he could locate it again, but “somehow we never got around to making the trip.” That second dugout, Chaffee later learned, “was pulled from the pond by someone and left on the rocks below the little dam” ca. 1970. Already badly deteriorated, it would then have quickly rotted away.

These Adder Pond dugout canoes were not alone. Another Andover dugout was preserved in an early photograph about a hundred and fifty years ago.

In the spring of 1869, Col. John B. Bachelder, a prominent American painter and photographer, today best remembered as the man who for decades painstakingly documented and analyzed the entire Battle of Gettysburg and was largely responsible for preserving and memorializing the Gettysburg Battlefield, set up shop in Andover Center for a brief period as a stereoview photographer. He was part of a wave of photographers and especially stereographers who, after the close of the Civil War, began celebrating and publicizing the beauties and grandeur of the White Mountains, the scenic lakes and waterfalls of the state, and the features of its scattered towns and farms. Soon enough Bachelder became an even more direct proselytizer for the new business, tourism, that was now beginning to transform northern New England, writing and lavishly illustrating (with one hundred engravings) a book, Popular Resorts and How to Reach Them (1873), that quickly went through many editions and became one of the great, seminal guidebooks for vacationers in New England.

Bachelder was himself a New Hampshire native (born in Gilmanton), and had earlier in his career devoted much of his professional life to painting scenic vistas of New England towns. (Many of his works may be seen at the New Hampshire Historical Society.) While many of his photographer competitors focused their attentions on the more spectacular vistas of the White Mountains, Bachelder instead devoted himself to mid-state scenes, producing several series of New Hampshire views, particularly “Local Views in the Vicinity of Kearsarge Mt.” (our Kearsarge, not the northern one). His stereographs provide superb visual documentation of Andover, Wilmot, New London, and Mount Kearsarge as they appeared in 1869.

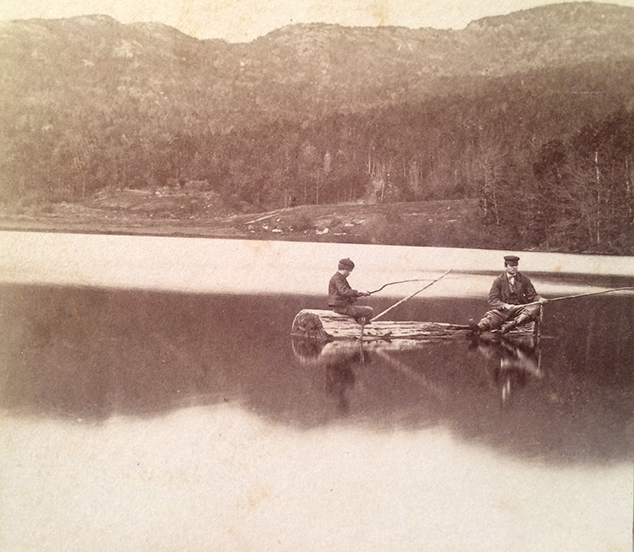

One of Bachelder’s most tranquil Andover stereoviews was titled simply “Cole Pond.” Probably taken in the early spring (the trees in the background are still leafless), it shows two young men out in a boat on the pond, with Ragged Mountain’s irregular outline providing a stark backdrop that is also reflected from the pond’s surface. The men are holding fishing poles, one of which is a branch so crooked that it must have been makeshift; they have a third pole set out, too. Their boat is unmistakably a dugout canoe.

Dugout canoes were not very portable; this one would have belonged exclusively to Cole Pond, even as the AHS’s canoe belonged to Adder Pond. The two canoes are of similar design, with truncated sterns, but very clearly these are two different boats: The Cole Pond canoe is made from a larger log, its stern is cut more nearly vertically, and its stern seat (from the tip of the stern to the beginning of the dugout cavity) is noticeably longer.

Nothing more is known of this canoe that once belonged to Cole Pond. Probably this boat, like most of its kind, was stored underwater during the winters and finally decayed there. The pond was later (circa 1902) dammed and enlarged from nine to fifteen acres, so that the old canoe hulk would thereafter have been hidden even deeper underwater. Its appearance in this one 1869 photograph is a reminder that, in the late eighteenth century and even well into the nineteenth, the presence of a dugout canoe on a local lake or pond could (and did) go without saying. There was probably a dugout canoe in use on most of the ponds in Andover, and likely more than one on the bigger ponds and lakes. Our “Settler’s Dugout Canoe” is a rare survivor; but it once had lots of company in town.