The old Center Road was built about 250 years ago and played an important role in the settlement and development of Andover. This road is on the northern side of Sucker Brook and Hogback and more or less runs parallel to Route 11 in the area near our house. Today we know part of this road as Hoyt Road, and it dead-ends at the top of the hill. But like so many roads in town, this was not always the case.

Prior to its incorporation as the Town of Andover in 1779 (known previously as Brownstown, Emerystown, and New Breton), and up until 1828, the town’s total land area was much larger than today. Its eastern boundary extended all the way to the Pemigewasset River. Thus, most of present-day West Franklin was once a part of Andover – including Chance Pond (now known as Webster Lake).

In 1828, the Town of Andover was ordered by an Act of the General Court to give up eight square miles of its territory. This land, when combined with parcels from Salisbury, Northfield, and Sanbornton, would form the new town of Franklin. About 50 families who had settled along the Pemigewasset River and Chance Pond in Andover were now suddenly residing in Franklin!

Building Center Road

According to John Eastman’s “History of Andover,” the proprietors of this early territory arranged for the building of a road through their land in order to encourage settlement. The first road built followed the western banks of the Pemigewasset and Merrimack Rivers, in a northerly direction from Stevenstown (later called Salisbury). The road was cut through by Colonel Blanchard in 1754 and was cleared of bushes in the summer of 1762.

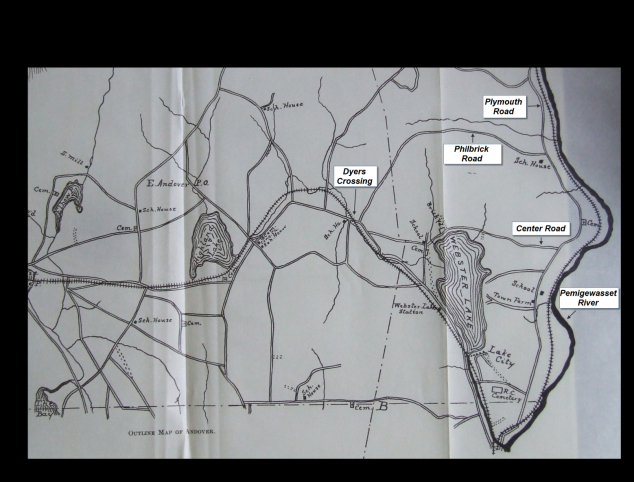

The road has been known by various names, including the Military Road, the Plymouth Road, and the Coos Road. Today, it is commonly referred to as Route 3A, the River Road, or the Hill Road. I was surprised to see it marked as the Pemigewasset Valley Road in my 2003 atlas.

Even before the above road was completed, plans were being made to cut and clear a road from this area of the Pemigewasset River over to Loon Pond (now known as Highland Lake). The road went around the northern end of Chance Pond (Webster Lake) for about two and a half miles. Next, it climbed up and over the back side of Hogback, which was referred to as the Great Hill.

The road then went down the hill to what later became known as Dyers Crossing. From there it continued on to the village of East Andover, following a route similar to the one later taken by the railroad (closer to the brook than today’s Route 11).

This road became known as the Center Road and ran in the same general area as today’s Lake Shore Drive (from Route 3A) and Apple Farm Road in Franklin, and to Hoyt Road in East Andover.

It’s easy to see how the Center Road was named: look at an early map of the land area which would later become Andover. This early road ran east and west near the geographical “center” line of the territory as defined at that time.

After 1828, and as other roads were built, the Center Road became the northern-most road of four possible routes between East Andover and Franklin. The others were the Brook Road, Marston Hill Road, and Flaghole Road.

Modern Times

The everyday use of the Center Road declined a great deal after the completion of the Brook Road in 1824. Even though the newer road had its problems, its route was shorter, more direct, and less challenging than the old road.

The Center Road’s biggest handicap was its steepness, which made it difficult to maintain. As more and more automobiles replaced the horse and buggy, the Center Road was used less and less.

I’m not sure when the eastern section of the road was discontinued, but I don’t remember our family ever using it. It was, however, one of the back roads I enjoyed riding on with my future husband Bob during our “jeeping” days!

Even though this road was once called the Center Road, I don’t remember ever hearing it called by that name – or by any other name, for that matter. Our family usually referred to it as “the road going over the hill by Clarence’s” (a cousin who lived at the top of the hill).

During the ’40s and ’50s, and maybe even later, there were two houses (since torn down) on the eastern side of the hilltop, which were in Andover. Everett Wilson, his wife Rose, and daughter Irene lived in the upper house, and Everett’s brother Bill lived a little farther down the hill.

When Irene was of school age, she walked all the way from her house to the Dyers Crossing School. Being an only child, it wasn’t uncommon for Irene to suddenly appear at our door, looking for one of us to play with her. This was after having walked across lots and through the woods to our house – a very long way!

Pasturing Our Cows

As our family grew in size, so did the number of cows we had. Our barn had room for only six cows, but we often had more than that (counting heifers and calves) during the three seasons of the year when they could be outside.

Before long our small pasture wasn’t large enough to sustain so many. My mother’s cousin, Clarence Rayno, owned the Center Road property at the top of the hill. His land abutted ours on the brook side and Last Street to the east, and included the Clay Bank or Hogback.

Clarence was using some of his land for his own cattle, but not all of it. My father and Clarence came to an agreement, which allowed my father to use the remainder of the land for grazing our cattle. When I think of it now, it must have been very difficult for my father to fence in and maintain this large, hilly area of land.

My father included a wooden gate in the fence on the other side of the brook near our barn. When the morning milking was completed, the bars in the gate were lowered, and the cows were free to wander off to greener pastures.

The area immediately across the brook from us was very hilly and wooded. In order for the cows to reach their grazing area, they first had to make their way up a steep, zig-zag path.

There were two main grassy areas, which were separated by more woods. We used to call these areas First Pasture and Second Pasture. As evening milking time approached, the cows usually came home by themselves. If they didn’t show up on time, one of us would volunteer – or more likely be appointed – to go find them and drive them home.

We hoped they’d be in the first pasture, and not the second, as the latter went all the way to the Center Road. Usually though, “going after the cows” was a chore we didn’t mind doing. It was good exercise, a pleasant walk in the woods, and we got to enjoy the sights and sounds of nature.