This article is re-printed with kind permission from MetroWestDailyNews.com, where it was posted on December 26, 2015 at 10:25 PM. It begins with an editor’s note that “Mr. Know-It-All is an occasional feature in which we answer reader questions about local history. Got a good question for Mr. Know-It-All? See the e-mail address at the bottom of this story.”

A colleague recently visited Sturbridge Village, where she was informed that Richard Potter, the first African-American magician, was born in Hopkinton, Massachusetts, in a section of town that is now Ashland. Potter is also credited with being the first American-born stage magician and ventriloquist.

My colleague thought these revelations might interest Mr. K. Well, you don’t need a crystal ball to divine that she was right. So here we go. Hold on to your magic wands.

Information for this column comes from the African American Registry, The Root, The Scottish Rite of Freemasonry and Magicpedia Web sites. The Root article was penned by Harvard University Professor Henry Louis Gates Jr. and freelance writer Julie Wolf. Gates is also chairman of The Root.

Richard Potter was born in Hopkinton, Massachusetts in 1783 on the plantation of Sir Charles Henry Frankland, a British tax collector who coincidentally was the subject of Mr. K’s column last month. Some online sites list Frankland as the father. Others place this paternity in doubt, and since Frankland died 15 years before Potter was born, that doubt is well earned. Hopkinton church records list the father as George Simpson, according to Magicpedia. Potter’s mother is described as a black servant on the Frankland estate named Dinah. One site has Potter being born in New Hampshire. He actually died there, but we’re getting ahead of ourselves.

At the tender age of 10, Potter set sail for England as a cabin boy. “Once there, he met a Scottish magician and ventriloquist named John Rannie, and he was captivated,” according to The Root article. “For years they performed in Europe, but in 1800 they traveled to America, joining a traveling circus and crisscrossing the North and South. (As Jim Haskins and Kathleen Benson explain in their book Conjure Times, Potter was able to travel safely in the South because, in his assistant’s role, he was perceived as Rannie’s servant.)

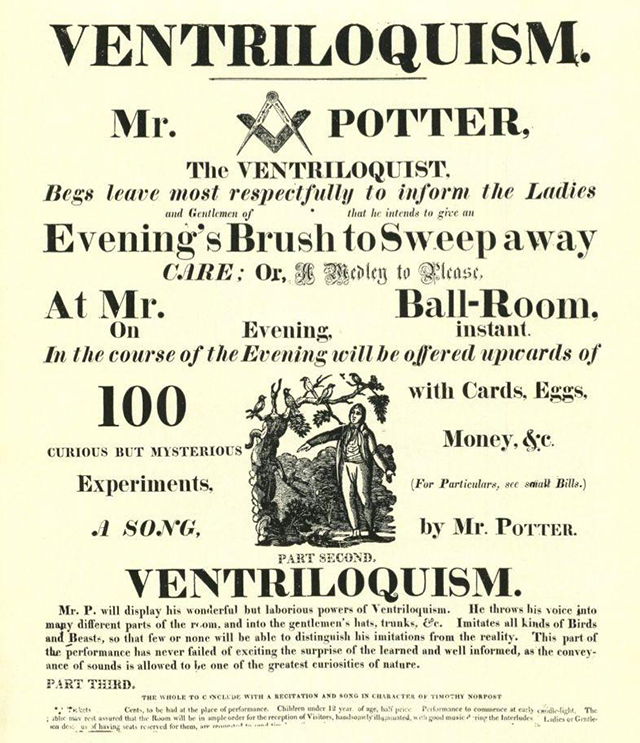

“In 1806 Rannie introduced live drama into their show, with Rannie and Potter performing most of the parts. The following year, Potter and Rannie took their act to Boston. In 1811 Rannie retired and Potter went solo. Self-promoted as “An Evening’s Brush to Sweep Dull Care Away” on broadsides that displayed the Masonic insignia (he was a member of the first African Masonic lodge in Boston), Potter’s shows were a huge hit, and he sometimes earned as much as $250 a performance (more than $3,000 in today’s money).

“His illusions never ceased to amaze. In one trick he climbed up a rope or an unraveled ball of yarn – outdoors and in front of onlookers – and appeared to vanish into the heavens. In another, he crawled through a log that appeared hollow; on closer inspection, spectators found that it was solid. Although Potter and his wife, the dancer Sally Harris, built a mansion on 175 acres of land for themselves and their three children (one of whom, in a happy coincidence, was named Harry, like that other famous Potter magician) in Andover, New Hampshire, he was an itinerant performer.

“From 1818 until 1831 he dazzled audiences up and down the East Coast. By the time he was 50 years old, in 1833, he had stopped performing magic, focusing on ventriloquism. He died shortly afterward in 1835. Although his house no longer stands, Richard and Sally Potter’s graves remain in Andover, and the town maintains a commemorative plaque in a part of town still known as Potter Place.”

The article concludes by noting that in 2014, Kenrick “Ice” McDonald was elected the first African-American president of the Society of American Magicians, an organization founded in 1902 by Harry Houdini, who was reportedly a Richard Potter fan.

As a ventriloquist, “Potter could skillfully throw his voice, especially using bird sounds,” according to the African American Registry. “Whether he was the first to use a ventriloquist’s doll or dummy isn’t known.

“Potter’s prestidigitation with eggs, money, and cards was considered of scientific interest, and he often performed at the Columbian Museum in Boston. He could throw knives and touch a hot iron to his tongue, walk on flames, and dance on eggs without breaking them. He performed in New York and all over New England.”

Potter purchased the aforementioned mansion in 1814. “The Potter estate consisted of several rooms on the first floor; the second floor was said to be one big room,” the registry site continues. “The Potters would have lavish dinner parties at their home, where he would entertain.”

After their deaths, the couple was buried in the front yard of their estate, but the house burned down. Their graves were moved to their present site in 1849 to make room for a railroad. All that remains to this day is a small plot with their gravestones, the registry site concludes.

According to The Scottish Rite of Freemasonry, Potter’s wife Sally was a Penobscot Indian. When Potter started his solo career, she served as his assistant.

“Because of his dark complexion, Potter was often thought to be an American Indian or Hindu, all of which added to his air of mystery,” the site continues. “He was described in advertisements as a ‘Black Yankee.’ He sometimes dressed in a turban and performed as an Asian or introduced his wife (accurately) as an American Indian. Potter took full advantage of his perceived exotic appearance and fueled the mystery over the origin of his birth by claiming to be the son of Benjamin Franklin. (Although Franklin was known to be quite the ladies’ man, he was out of the country at the time of Potter’s conception.)

“Magic acts performed by Asians and Africans were successful because of the lingering belief of the public in ‘real magic’ from mystical and exotic parts of the earth. Potter, the consummate showman, took advantage of these folk beliefs and gave his audiences what they wanted – mystery, exoticism, and a smashing good show. In 1817, during the depression of 1815 to 1820, he was confident enough to increase his admission to a dollar, at a time when an unskilled laborer earned about 50 cents per day.

“While he performed primarily in New England, Potter and his wife played most of the United States. In Mobile, Alabama, he was refused space at an inn because of his race. Despite his run-in with prejudice during his stop, he made $4,800 – about $55,500 today. Not feeling safe with that much money, he left the city in the middle of the night in the opposite direction of his next venue.”

After Potter’s death, his son Richard Jr. continued his father’s profession, although unsuccessfully.

The Manchester, New Hampshire, “Ring” of the International Brotherhood of Magicians is named in honor of Richard Potter.

According to Magicpedia, for one of his tricks, Potter would enter an oven – we assume a large oven – with raw meat and remain in there until the meat was cooked. We assume he would emerge unscathed and not charbroiled. He also handled and swallowed molten lead. Kids, don’t try this at home.

Mr. Know-It-All, a.k.a. Bob Tremblay, can be reached at 508 626-4409 or RTremblay@nullWickedLocal.com.